drunk ethnography #6: NIGERIAN INDEPENDANCE

roni goes to play piem's nigerian independence party

04/10/2024

64 years of independence and Nigeria has very little to show for it. Plagued by poverty, corruption, and violence, it’s no wonder that those on the continent look on with contempt for the annual celebrations of the privileged western diaspora. Independence carried the promise of a brighter future for Nigerians free from the tyranny of British rule but formal decolonisation was not the death of colonialism. The empire was simply reborn with successive governments acting as neocolonial compradors in the continued prioritisation of western state and corporate interests over black lives. Nevertheless, we the children of the diaspora - evading the abjection of life in the ex-colony/neocolony whilst encountering the colonial boomerang effect when the anti-black sociospatial organisation instituted in the colony is reiterated in the heart of empire - wish to dance.

I’d have been at the club one way or another on a Friday night. In the party landscape, Nigerian independence seems to be nothing more than an excuse for London’s biggest ethnic group to totalise the dance floor completely. We all know by now that afrobeats has gone from being the musical gem of West Africa to a global phenomenon with Nigerian artists now selling out shows around the world. This growing influence has unsurprisingly been reflected in the prevalance of afrobeats in parties catering to black audiences as well as those for broader audiences. In this sense, the only thing that really separates independence weekend from any other weekend in the city is an inflated sense of pride in Nigerian culture. The self-described ‘African giant’, Nigerians are notoriously cocky about our cultural significance and pointing out this arrogance seems only to fuel our egos. You might look simply to the online alliance of Africans from all over the continent against Nigerians when the national football team made it to and ultimately lost the AFCON finals earlier this year as evidence of our widely felt annoying presence. We are an insufferably loud, unwaveringly pompous, seemingly omnipresent people. Needless to say then, a night dedicated to celebrating Nigerians and Nigerians alone is something of a wet dream for Nigerians like myself eager to revel in the country’s expansive musical history.

I knew I wanted to go to a Nigerian independence party but I didn’t know which one. I can be rather snobby about parties. Though I fight the urge to stereotype partygoers and organisers, there’s a certain degree of categorisation necessary to understand what I’m getting into and minimise the prospects of ending up on a shit night out. I could go to a more mainstream party, a party where your average uk black would go (see drunk ethnography #1 for more on the uk black). There I would be sure to hear the usual afrobeats hits from greats like Wizkid, Asake, and Rema, but as afrobeats parties aren’t my usual scene there’d be a degree of anonymity I wasn’t so sure I wanted. Some people hate seeing the same people at every party but, for me, half the fun of going out is knowing I’ll certainly bump into friends who will introduce me to friends. The more you’re in a particular scene the more your social circle expands. Each event is an opportunity to tighten bonds with potential to transform a smoking area chat in the dark of night into a friendship in the light of day.

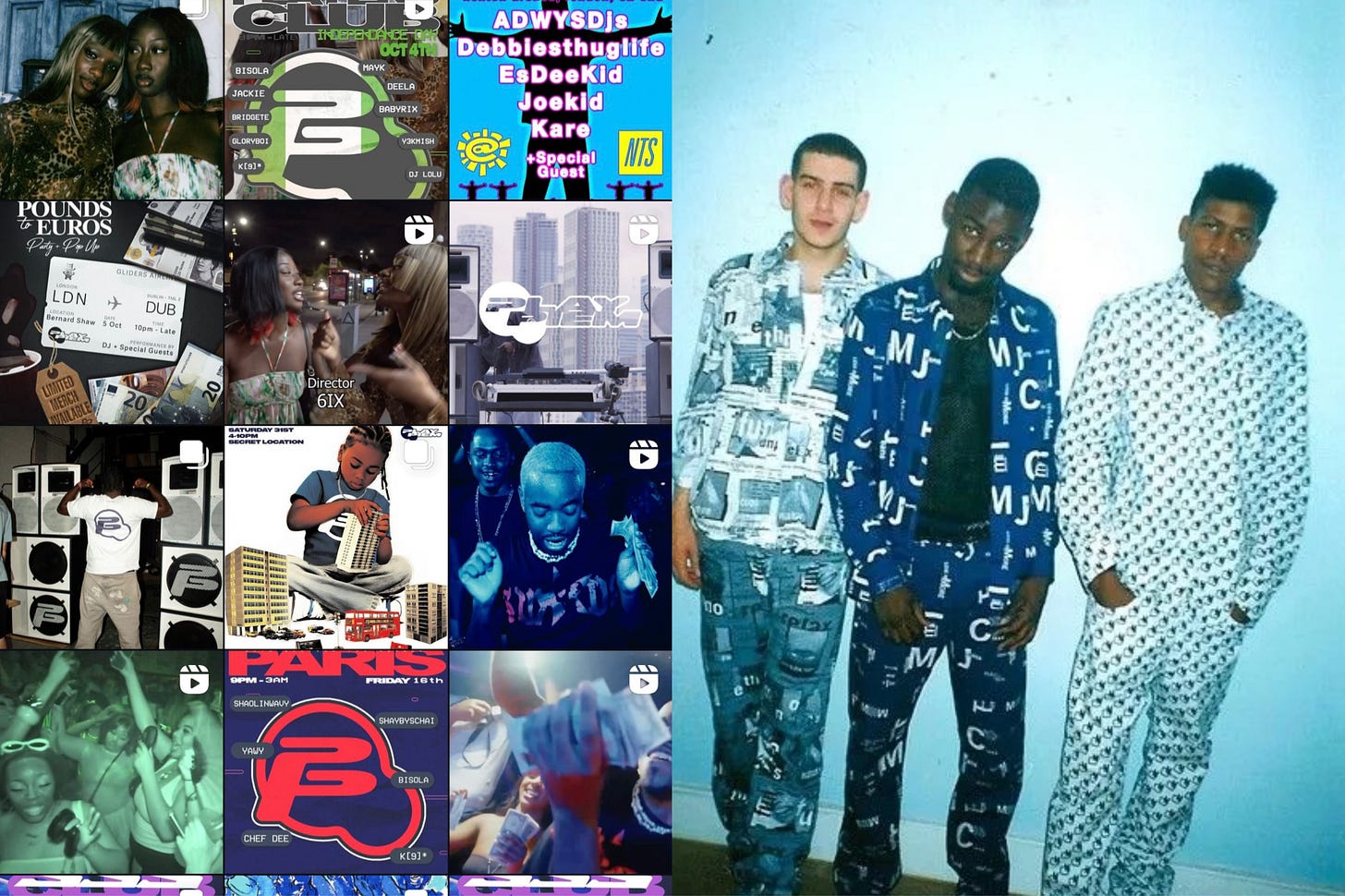

Play Piem seemed more my scene. The playground of the uk underground, the collective draws in people that like their parties to have the flashiness of a 2000s US hip-hop music video slightly inflected with the grittiness of London’s council estates. On their Instagram this comes across in wads of cash, glistening chains, and twerking girls in mini skirts washed in cool blues and purples, or the uncanny greyish green of a night vision camera that bathe these glamorous American aesthetics in the cold light of Britain’s concrete jungle. Indeed, the emphasis on maintaining a high standard of glamour enforced through party dresscodes, social media visuals, and the occasional presence of strippers in the club harkens back to the aesthetics of the UK garage scene in the 2000s. Similarly influenced by increasingly globalised black American style along with the extravagance present in African and Caribbean cultures, these UKG parties could not be attended without securing the finest garments. There you’d find mandem in full on suits and absolutely no trainers allowed, gyaldem in sexy dresses and eye-wateringly high heels. When you were stepping out you had to impress. This was an expectation that has since dwindled in most clubs but perhaps the African urge to adorn the body has persisted with the appearance of highly aestheticised events like Play Piem.

What then does Nigerian independence look like in this black Atlantic convergence of the US and UK? Knowing the pervasiveness of Nigerians in the London music scene I was certainly intrigued to see. I’d hoped that I’d get to hear the sounds of Nigeria’s flourishing “alté” music scene filled with young, (often annoyingly wealthy) artists making a fusion of afrobeats, dancehall, hiphop, reggae and alternative rnb. Lagos and London’s alternative music scenes fused. This was certainly implied by the Nollywood dresscode. A style beloved by young Nigerians in Nigeria and Britain alike. Favoured for the way stars of Nigeria’s film industry cultivated an aesthetic in the 2000s that adopted black American fashion of the same era infusing it with a distinctly Nigerian audaciousness. The Nolly babe walks with her head held high. She speaks her mind and she doesn’t take shit from anyone, especially not a man. She is excess. Her skirt is too short, her lip liner is too thick, her eyebrows are too harsh. Even the acting is over the top. She is the embrace of unrespectability, the complete disregard of European bourgeois idealised femininity. I hoped to embody her raunchiness with a denim mini skirt, a green knit crop top hugging my skin (a nod to the national flag), sparkly silver tights (this is not Nigeria after all), beige Isabel Marant sneaker heels, and the star of the show, my new cropped fur coat. Dress to impress. Dress in excess.

As if it wasn’t bad enough that I’d have to venture south of the river for a party, the venue was in the middle of bumfuck nowhere. How the fuck do you get back to north London after a night out in West Dulwich? There was only one way to find out. Following a 40 minute bus ride from Waterloo with the aid of a chilli mango buzzball, my friend, Ellis, and I arrived just in time for last entry. Now I don’t want to complain (that’s a lie, I love complaining), but I distinctly recall that when the event was first announced last entry was 12:30pm with the party set to end at 4am. It was on this basis that I forked out the £15 for a ticket. But a day later when I went to look at the event flyer on their Instagram, it was nowhere to be found. I thought nothing of it until a new poster appeared with a new last entry of 11pm and a curfew of 2am. 2AM???? Considering nobody in their right mind would arrive at the 9pm start time, we’d be there from 11pm - 2am. Now factoring in that the dance floor rarely gets really popping before 12pm at any function, we’re now looking at a mere 2 hours of partying. £7.50 an hour without even adding on the cost of drinks at the bar.

The club has its own temporality. Time moves faster in the humidity of the dance floor and the chilly air of the smoking area. The music adds to this acceleration as DJs play just a minute or so of each song before swiftly taking their listeners to another sonic destination. Unbeknownst to you as you bounce around this nighttime maze, getting lost in music, drinks and conversation, the clock ticks rapidly. In the blink of an eye 11pm is 1am and, in this instance, 1am marks the beginning of the end. You get the sense that you’re running out of time. There is a sudden awareness of the impending doom of being cast out into the streets to fend for yourself. The warm glow of the club behind you, you are left on the street with one question on your mind. Did I have a good time?

It’s difficult for me to answer that question. I mean, I know I didn’t have a bad time but you could give me some tequila shots and music and I’d have fun kicking it with a rat so I’m not sure that is a sufficient indicator of a good party. Stylish 20-somethings filled the Georgian mansion in which the independence celebrations took place, chatting in stairwells, hallways, and by the bar. Ellis and I were among the early arrivals to the dance floor. By the DJ you would find those of us willing to move our bodies no matter how few people joined us. I did so with the particular enthusiasm of a tipsy music lover who simply cannot help but give it her all any time she enters a function. When I dance, I dance like it’s my last night on earth. This is my inheritance from the Nolly babes who came before me, who didn’t care what anyone said about them. Gleefully using the space afforded by others’ lateness or perhaps reluctance to entering the dance floor as my own personal stage to strut, gyrate my waist, and rap along to each song. I danced so hard that I completely forgot the reason I’d come to the party in the first place. Suddenly, I emerged from a hype haze and remembered. Wait a minute this is meant to be a Nigerian independence party, why the fuck am I listening to US rap?

I made my way to the smoking area where I was commended for my high energy performance inside. That I’d had a good time was certainly clear to me from the sweat accumulating under the fur coat I’d refused to take off. Dress to impress. Dress to excess. But my realisation lingered. I remained haunted by a spectre of the Nigerian culture displaced by the global domination of black American culture so that when I returned inside once more I danced, yes, but I danced now with the weight of expectations of the motherland. With a sense of yearning for the sound of Yoruba to infiltrate the airwaves. To say that no Nigerian music played that night would be a gross misrepresentation but as the clock struck 1am, the bar was abruptly closed and the people were all ushered into the dance hall for the last DJ sets of the night I had expected to be all but transported to Lagos. Instead I was met with US female rap to get the pretty girls lit and bashment to get them whining their waists. As god is my witness, if I hear the words “Introducing Vanessa Bling as Gaza Slim” one more time this year I am going to climb atop the CDJs and piss on them.

The overhead lights flickered on and off signalling the end of the night at barely 2am and security did not hesitate to hastily usher partygoers off the premises. As I made my way out I bumped into an acquaintance who asked if I’d had a good night to which I screwed my face and remarked “They said Nigeria and I’m hearing Jamaica”. He laughed. I think I now understand how Caribbean people feel when they are told a party will be playing bashment and are met with a bunch of afrobeats. It ain’t no fun when the rabbit’s got the gun. Standing on the dimly lit, forested street I looked back at the mansion behind me. Alcohol wearing off and the party itch left not quite scratched after only a couple hours inside, the large white building no longer possessed the potential for excitement inside. It just looked gaudy. Garish. Its tall white walls a tasteless display of wealth - like all mansions are - serving to delineate rich from poor, white from black. How many servants once filled this house? How did its various owners from the 18th century to the present reap the rewards of life at the centre of empire? One can easily imagine a reality in which a Yoruba person like myself was taken from their home and shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas where they worked on a sugar cane plantation that would provide sugar for tea served to the owners of the Belair estate. Happy Nigerian Independence.

Our inheritance in the diaspora is to always have history follow and precede us1 which is to say that we cannot evade the past for it reappears always to rupture the present2. Haunting the halls of Belair House are the souls of those who lived to die3. The slave, the colonial subject, the Nigerian citizen for whom life was never an option as their bodies and desires were subordinated to the wills of whiteness. Do not mistake this for mere condemnation of the diasporan dancer, I am one of them after all. I danced amongst those souls. Rather, I wish to call attention to the potential limits of a pleasure-filled politics. Dancing is not liberation. Pleasure is not liberation. They coexist with pain often on an immense scale so that the image of diasporan dancers might momentarily disrupt the sociospatial organisation of this normatively white space but does not overthrow it4.

Indeed, the mansion towering over me as its borders were doggedly defended by black henchmen security guards made me acutely aware of my powerlessness as a party girl (gender neutral) and as a black. As a black, the spectral light of its white walls in the dark of night reinforced my placelessness. We blacks did not belong on this property nor did this property belong to us. In the middle of nowhere with no place to continue our pursuit of pleasure at this hour too early to end the night but too late to start the night anew, Ellis and I walked somewhat aimlessly until woodland became the brick and mortar of a chicken shop. As a party girl, I wondered how this party had become so consumed by the aesthetics of wealth that we had neglected the party itself. Perhaps if the allure of a mansion party had not been so strong we might have danced instead in a venue that would’ve welcomed us past 2am. And perhaps if we had not been so enamoured by the Nolly babe’s physical glamour and sex appeal we might’ve considered the content of her soul. There we might’ve heard the rhythm of the West African drums to which her spirit moved which made her attuned to the culture of her African American siblings across the Atlantic but made each gyration of her waist unique. Maybe then we would’ve known the significance, indeed the necessity, of Nigerian music on the dance floor.

I say ‘we’ but there is no we really. I had no say in the curation of this event. I try not to view myself as a party consumer. I believe that the party girl and party organiser operate in a dialectic with each making the other’s and the party world’s existence possible. But what choice do I have when I am alienated from my labour? When my dancing is made into commodity, independent from me, to be sold on the marketplace of nightlife. The image of the diasporan dancer is paraded across social media as a hot product you too can purchase with another £15 ticket to another event. And so the dancer’s activity is not her spontaneous activity, it belongs to another, it is the loss of self. As the diasporan dancer is estranged from her nature, as her pleasure is held in the hands of the privileged few who dictate the use of her body through control over the music and venue of the party, she lacks more and more. She goes home frustrated that she paid £15 to hear Glorilla and there was nothing she could do about it.

I close this drunk ethnography by calling for a dictatorship of the party girl. Tear down the hierarchy that places organiser above dancer. Demand that your party overlords are made accountable to you. The party is not a gift bestowed upon you, it is as much your creation as it is the organiser’s. Assert your right to create it. Boo the DJ. Boycott the dance floor. Punch the party photographer (don’t do that). Write a self-important blog where you use Marxist theory to complain about a night out. Or start the party you want to see in the world. Whatever you do, go forth into the night my fellow black club rats and make a place for yourself by any means necessary. Nothing to lose but your mild disappointment.

Brand, D (2002) A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging, Toronto: Vintage Canada.

Sharpe, C. (2016) In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Durham: Duke University Press.

CeeCee (2024) To Live In Limbo. Available at:

Brooks, S., Cruz, A., Jones, A., (2023) Black Feminist Uses of the Erotic: A TBS Roundtable. The Black scholar. [Online] 53 (3–4), 4–18.

Defo agree that people are too stuck on the idea of leisure being revolution; music/culture can narrate the story of change but they are not the change